Today I left Zamora, a really lovely town, and crossed over a Medieval bridge to my next destination, which is Puebla de Sanabria, just a bit over 100 kms away.

As I tend to maintain a rather leisurely pace of around 20kms an hour on average, this is another short riding day. I try to keep things as fluid as possible, in the event that I detain myself over some detail, or I have a particular interest in some location. The elevation chart indicated that today's riding profile had elevation gains of less than 50 meters until Tabara, where I stopped for lunch, and after that there was a mild 200 meter gain over a 40 km stretch until reaching Puebla de Sanabria, where I had booked a "pension rural" for the night. Essentially, a perfect day of cycling in an almost windless setting, temperatures in the low 20's, and mostly flat terrain. Thus I will spend some time and write a bit about how I travel, and why.

Usually, I get up around 8:00 or so, and have some churros with chocolate at a local bar, typically in the main square of whatever town I happen to be in. Then I'll cycle for two or three hours and stop at another town and have a break, typically just some mineral water and some olives with a bit of bread, also typically at a sidewalk cafe in the main square. There is a consistency to Spanish towns that predates fast-food, 7-11's, and multinational chains by thousands of years: the main square always contains a fountain or a statue in the center. At one end is a church or cathedral, at the other, city hall. All along the periphery in the arcaded colonnades are shops, bars and restaurants, thus without having to do a great deal of searching, all the amenities I am likely to need are close at hand and obvious.

Typically, I usually don't even look at the menu anymore, just ordering some mineral water, some shrimp fried with garlic, or some olives, or manchego, or fried new potatoes in olive oil with garlic and onions. Every bar has the same things, it's always delicious, dripping with olive oil, and exactly perfect for a quick snack. Tapas are a blessing for the solo traveller.

Today, my first stop after breakfast was Tabara, a reasonably insignificant town of a few hundred people. I say insignificant because to the average, jaded North American there is absolutely nothing here that would catch their interest. For me, on the other hand, these tidy little towns often hold some detail which makes them magical. In Tabara, for instance, in the year 220B.C., Hannibal showed up with 22 African elephants and stayed for a month. Other interesting things of this "insignificant little town" include a Mozarabic mosque from the 9th century, long ago converted into a church, and most interesting to me, the remnants of a Visigoth church from around the 6th century. As is the usual case with the adaptive reuse of buildings throughout history, the portico and tower have been added at some later date, probably around the 11th or 12th century, judging by the construction technique and design. The town appears to have been far enough south that it was almost continuously changing hands between the Moors and the forces of Christendom, being pretty much on the front lines.

I always make it a point to read as many of the inscriptions as possible, since out of tiny little towns such as these have come historical characters that have later had a profound influence on history.

After lunch I pushed on for a few more hours over a landscape of scrubland punctuated by the occasional green field. Things are starting to get a bit greener, over all, and tomorrow I will be in Galicia, which is very green indeed.

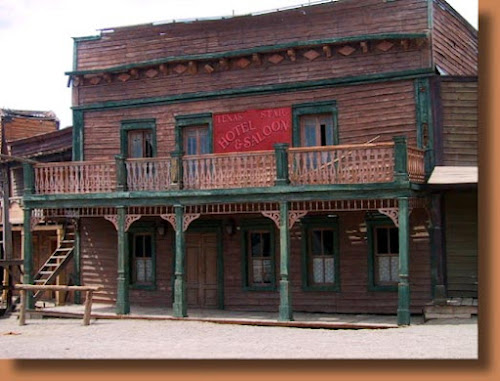

The final climb today was exactly at the very end of the ride, up to the fortified hill city of Puebla de Sanabria, a charming town where one could spend several days if so inclined, just relaxing and soaking in the atmosphere.

The town has a lovely main square at the very top of the hill, at the foot of the castle and the church, a lovely medieval pile in the Gothic/Romanesque style dating from the 13th century. The castle itself is much later, dating from the 1400's, and has been fully "museumized", which is to say, one can walk around and interpretive plaques describe the function of various architectural details. Usually these are aimed at the non-specialist, so rather obvious for someone like me who has studied medieval fortification technology in detail, but the fact that the site is well preserved is always a welcome touch.

My lodgings tonight are at a lovely "pension rural" which overlooks the main square.

The secret to travelling inexpensively in Spain is to always book ahead, even if only by one day, and always use a web discount service, such as Expedia.ca. Typically, a room at a 3-4 star hotel in Spain will cost around 60 to 100 euros if you show up unannounced. If booked ahead and online, however, the price drops to 30-40 euros, and often includes perks, like access to the breakfast buffet and free internet wifi. As well, since I'm travelling in the low season, nothing is ever booked to capacity, and the rates are significantly reduced from high season. Such is the case for tonight's place, which boasts high speed internet, breakfast, and one of the most comfortable beds I have ever slept in.

In general, the way I travel, though modest in terms of actual expense, is in other ways entirely decadent when compared to the hardships which typical pilgrims on their way to Compostela endure.

Typically they fend for themselves in markets, eating bread rolls stuffed with whatever hams, cheese or sausages are available, and on reaching the albergue, will go shopping at the local market and make up whatever the cooking facilities allow. A note on albergues: these are typically run by the municipality or the local church, or both, though there are private albergues as well. An albergue is essentially a large dorm room, usually but not always segregated by gender, and there are usually bunk beds, often as many as fifty to a room. As is expected with the communality which makes up the entire camino experience, meals are shared, stories are told, clothes are scrubbed, and essentially it is a step above sleeping under a bridge. Sheets typically are not provided, and though the system runs well as an honour based facility, since 1998, the minimum "donation" is 5 euros, though private albergues will charge 15 euros or more, depending on facilities. Doors typically close at around 10pm, so there is no possibility of late night excursions, meanderings, or for that matter late meals, and everyone gets kicked out the next day by 8:00am, and one is only allowed to stay for 1 night (as if anyone wanted to stay longer). Many do not have hot water, and only crude, again communal, showering facilities are provided.

I have nothing to prove by staying at albergues. I have been swimming in glacier cold lakes in the Chilcotin, and slept under the stars with little more than a blanket. When I was younger I would stay at the most ridiculous hostels because they were cheap. At this stage in my life, the comforts of a firm mattress, a bathtub with unlimited hot water, and a local fine eating establishment are far more important to my well-being than the comaradarie formed by fast friends on the camino.

This sort of hardship is also somewhat non-sensical from an economic perspective, since the cost of traveling using the albergue system, versus traveling the way I travel is inconsequential: a typical peregrino might spend 20 euros a day. I spend perhaps 60. However, I travel three to four times faster than they do, spending less time on relatively uninteresting landscapes, and relatively more time on historic monuments. There will be those that will argue that the after-dinner metaphysical discussions which take place at albergues is an important component of the trip. I would answer that I have been to several of these discussions, as I often pass by albergues in the late afternoon to get my credential stamped, and have often been invited to stay and rest for awhile. Almost invariably, the discussions have been about what is most missed, how much they're in pain, how their feet hurt, etc. etc. etc. Albergues, by and large, are for pilgrims in their 20's or perhaps 30's. Those of us in our forties will find far more interesting conversations with people of our own age, who rarely stay in albergues, but who I will often encounter in places which I frequent, namely, sidewalk cafes and fine local restaurants. There will be those that argue suffering and hardship are part of the Camino experience, and I'm trivializing it by approaching it like some 19th century English traveler in search of fine linens, exquisite clarets, refined cuisine, warm baths and fluffy towels. To these people I would say that suffering is over-rated. Pain is psychological, and suffering is a conscious decision. In the end, I will still have the same framed Latin certificate on the wall, but the memories of exquisite architecture, lovely hotels, and an appreciation of the local cuisine will be far more vivid to me than if I had done nothing but stay in nasty albergues and eaten ham and cheese sandwiches for a month.

Yesterday I had lunch with Heinrich and Frida from Dusseldorf, both retired teachers, who speak excellent Spanish (like most Germans, very crisp) and we had a lovely talk about the euro, and the future of European unity. Like most Germans, they are seriously wondering if the economic benefits of easier trade are making the tradeoffs of bailout payments really worth it. I was of the opinion that in the long run, Germany would probably leave the euro, since the northern way of thinking, that is, living to work, was irreconcilable with the southern way of thinking, which was working in order to live. While milage may vary ( the rest of Spain calls Catalans "the Germans of Spain", and in terms of transfer payments this is painfully true) there are economic basket cases like Greece that are beyond hopeless, and will never be anything like what a modern, industrialized, secular western democracy should be like. The Greeks simply do not have it within themselves as part of their national character not to find ways to game the system.

Afterwards I rode with them for awhile and when they stopped some kilometers ahead, I bid them a good afternoon and continued. I took careful note of their bicycles and equipment, most of which I was familiar with, having done quite a lot of online shopping in European bicycle shops in order to upgrade my own bicycle. They both had enormous Ortlieb panniers, which, while being first rate in their quality, weigh a veritable ton. They also rode fairly heavy hybrid bicycles, which are very popular here in Europe, combining the ruggedness of a mountain bike, with the faster speed of a road bike. I think they may find these a bit delicate once they reach Galicia, however, but they may well plan on sticking to the roads rather than the camino. In general, most German bicycle equipment is built for durability, with little or no consideration for weight. It's all excellent quality, but stupendously heavy.

My own approach resembles early 20th century British touring kit. I wear wool breeks (+4s!) and long wool argyle socks, and I do not use panniers but rather just have a waxed canvas saddle bag which quickly detaches and converts into a valise. I take good care of my equipment, and the ruggedness of heavy canvas and leather is sufficient for the more genteel touring I am accustomed to. This set-up does not provide as much room as a pair of nylon panniers, but again, having so much room is just an invitation to overpack. I find that having just a complete change of clothes, some light rain gear, an extra pair of socks, and some minor toiletries and electronics ( like this iPad), is ample enough baggage: just a touch over 12lbs including the bag.

I have been asked what it's like traveling alone; many people who take on the Camino do so as a group of friends, or will meet up with people and travel en mass. In terms of finding spiritual meaning in the exercise of pilgrimage, such as it is capable of being found, historically pilgrimages were almost universally undertaken by individuals on their own, for obvious reasons, thus I question the sincerity or intent of those who travel as a group. As Leonardo da Vinci so elegantly put it:

"If you are alone you belong entirely to yourself. If you are accompanied by even one companion you belong only half to yourself or even less in proportion to the thoughtlessness of their conduct, and if you have more than one companion you will fall more deeply into the same plight."

Other keen long distance cyclists, such as T.E. Lawrence and later Henry Miller made the same observation; traveling alone is a luxury, and not a hardship at all.

Furthermore, the many hours of introspection inherent in traveling thousands of kilometers is conducive to some form of meditative flux, certainly, though the idea that this leads to some transcendent state of Christian piety is laughable for anyone accustomed to protracted periods of abstract thinking in an academic setting; I get more from listening to a good lecture on quantum mechanics than the most erudite sermon on the fallibility of the flesh. I have noticed that most pilgrims on the Camino, again, young people, invariably have earbuds firmly installed and are no doubt listening to the latest Metalica album. Again, let no one talk to me about authenticity with regards to bicycling the Camino. For me, transcendence is a secondary aim, and the pursuit is to strip away the accretions of semiotic Hyperreality, and enter that elusive state of perspective where magic is possible, stone carvings can come to life...

...animals can talk, music is only heard in churches, a horse and rider are the fastest way anyone can travel, and the ethereal blue light coming through a stained glass window is more than just a beam of sunlight hitting a pane of molten silica impregnated with cobalt salts.